Just a few years ago, the world watched in dismay as ISIS/Daesh publicly and ostentatiously destroyed or damaged structures from ancient Mesopotamia, artefacts in Mosul Museum, and Palmyra’s ancient Roman Tetrapylon and Roman theatre in today’s Syria. At the time, Marina Gabriel, from the American Schools of Oriental Research Cultural Heritage Initiatives (ASOR CHI), is reported to have said, ‘This destruction is almost unprecedented in recent history, and is particularly devastating for a region with extensive history that has impacted the world.’

Watching Notre Dame go up in flames this week manifested similar feelings of a sense of loss, though clearly a fire probably through neglect is different to destruction through a baleful ideology. What is interesting, however, is that a handful of days before the Paris fire, reports emerged from Iraq that the third-century Persian Taq Kasra had partially collapsed. Seemingly similar to Notre Dame, claim critics, neglect of some sort seems to be the reason.

Located not far from Baghdad, the former palace of Taq Kasra is said to be the ‘world's largest brickwork vault’ and a singular architectural structure. On a website dedicated to the ancient monument, Netherlands-based Pejman Akbarzadeh, who in 2018 made a documentary about the site, alleges that Czech conservationists were not quite the experts they appeared and did more harm than good. In this BBC interview (right), Akbarzadeh talks about his film.

Commentators and the general public rightly feel great pain at the loss of irreplaceable artefacts in the Notre Dame fire, and the Iraqi government joined other countries in writing to France to offer heartfelt condolence at the devastation the fire caused. Such solidarity is genuine and understandable, particularly from a country that has suffered so much over so many decades.

Critics, however, are asking why the Iraqi government is not doing more to protect its own – extensive – cultural treasures, such as Taq Kasra. On the one hand, it’s difficult to be overly critical of Iraqi authorities who are struggling to adequate provide water and electricity for all its citizens. On the other, there’s hardly a country in the world that matches Iraq for corruption.

And while such a state continues, the country’s hugely significant cultural legacy continues to decay.

-

August 2023

- Aug 29, 2023 Argentina's Andes: beauty and tranquility Aug 29, 2023

-

January 2020

- Jan 8, 2020 Surprised CSU grassroots rejected a Muslim? Jan 8, 2020

-

December 2019

- Dec 13, 2019 It’s not just MPs who you’ve lost Dec 13, 2019

-

July 2019

- Jul 4, 2019 Robert Andreasch, worthy winner of Munich journalism award Jul 4, 2019

- Jul 1, 2019 Munich police raid on refugee shelter leaves mother with broken arm and son arrested Jul 1, 2019

-

May 2019

- May 5, 2019 New Pinakothek, exhibition: Die Neue Heimat (1950-1982), A Public Housing Corporation and Its Building May 5, 2019

- May 1, 2019 Spotlight magazine - Munich’s Brits: a sporting community May 1, 2019

-

April 2019

- Apr 17, 2019 Paris and Taq Kasra, Baghdad Apr 17, 2019

- Apr 11, 2019 Denmark Apr 11, 2019

-

March 2019

- Mar 8, 2019 Passport decision time Mar 8, 2019

-

February 2019

- Feb 24, 2019 Business Spotlight: Brexit Britain Feb 24, 2019

- Feb 14, 2019 Munich's Fridays For Future Feb 14, 2019

-

January 2019

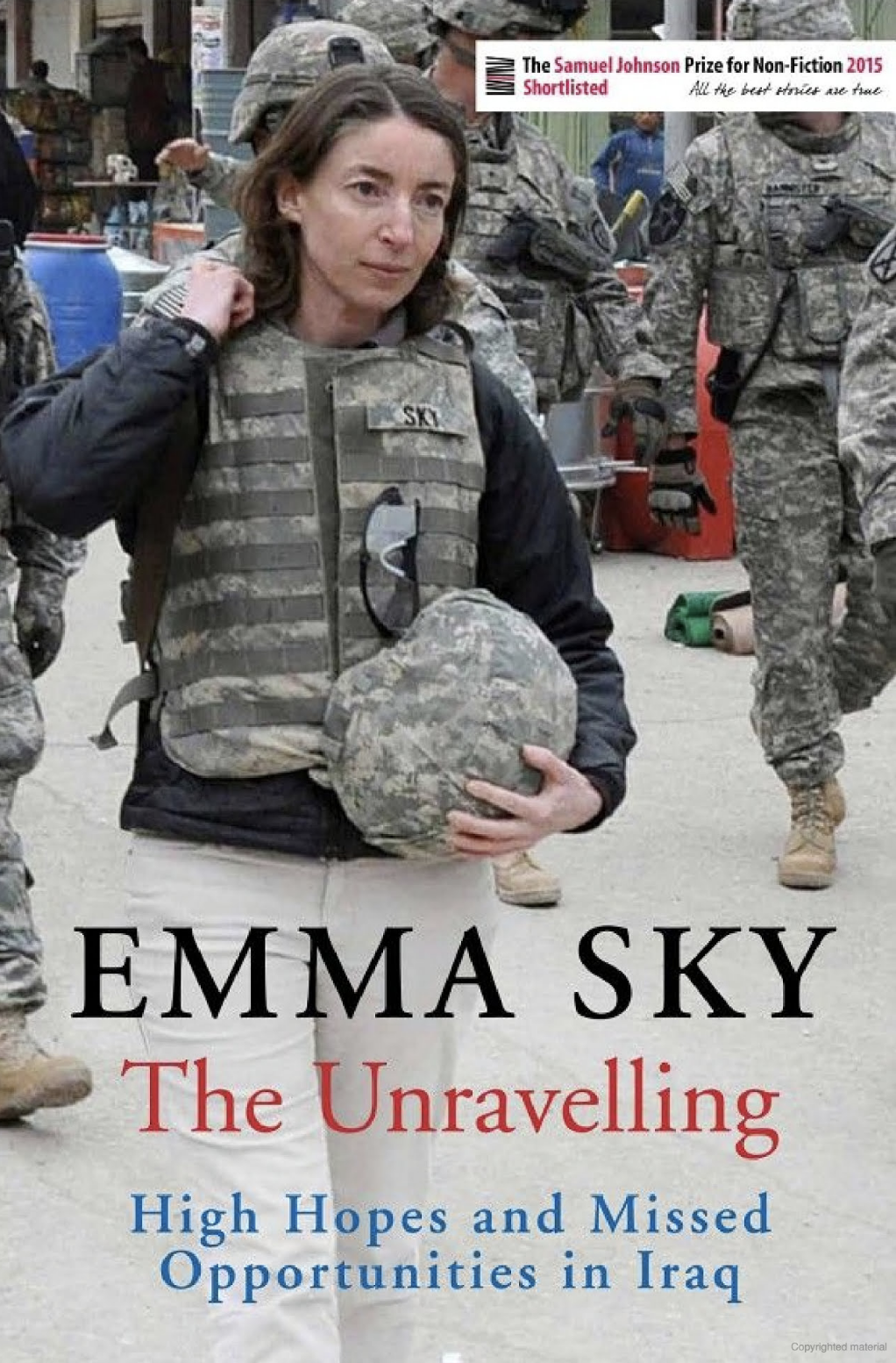

- Jan 28, 2019 Book Review: The Unravelling. High Hopes and Missed Opportunities in Iraq Jan 28, 2019

- Jan 15, 2019 Book review - John Robertson, Iraq. A History Jan 15, 2019

- Jan 1, 2019 Poverty Safari, Darren McGarvey Jan 1, 2019

-

December 2018

- Dec 28, 2018 Iraqi artist recreates 3D ancient cities Dec 28, 2018

-

November 2018

- Nov 28, 2018 Ireland: Waterford and the King of the Vikings Nov 28, 2018

- Nov 27, 2018 Spotlight: Pakistan Nov 27, 2018

- Nov 12, 2018 Business Spotlight: Israel Nov 12, 2018

- Nov 10, 2018 Business Spotlight magazine: South Korea Nov 10, 2018

- Nov 2, 2018 Thousands of dead fish ... the rivers of Babylon Nov 2, 2018

- Nov 1, 2018 Lacrosse interview – German and US players in Munich Nov 1, 2018

-

October 2018

- Oct 31, 2018 Book review: Alan Rusbridger, Breaking News. The Remaking of Journalism and Why It Matters Now Oct 31, 2018

- Oct 26, 2018 Food: Sababa, Munich's best falafal restaurant Oct 26, 2018

- Oct 19, 2018 CSU loss is a Green gain Oct 19, 2018

- Oct 18, 2018 Gozo's Ta Tumasa & hints of the Middle East Oct 18, 2018

- Oct 18, 2018 The Price of Plastic - For One Turtle Oct 18, 2018

- Oct 14, 2018 Visit Malta, stay on Gozo Oct 14, 2018

-

RT @BritishCycling: Cyclists aren’t the ‘scourge of the streets’. They are mothers, fathers, grandparents and children all doing their… https://t.co/DEYuaNlUYB

-

RT @krishgm: Former Trump campaign manager Corey Lewandowski doesn’t remember Wikileaks, thinks we’re having an election in two… https://t.co/BOjqH3wPLs

-

Imagine how the map would look if Munich had a fully functional, safe and connected cycle network. https://t.co/76wMhGTWkg

-

RT @mehdirhasan: Most UK news coverage of Muslims is negative, major study finds | News | The Guardian https://t.co/nsDFEpHFHX

-

RT @istanbuljoel: King's College Professor @jdportes talking a great deal of sense about immigration with solid evidence and useful h… https://t.co/2InqBY4ByJ